For almost a thousand years, Rome influenced the Church of England; Catholicism infiltrating and affecting just about every aspect of life: trade, contracts, marriage etc. A century before the Glorious Revolution, England, under the rule of King Henry VIII adopted its own form of Catholicism namely Anglicism. This was a major blow to the Pope and it fuelled fears that other countries may follow.

During King Charles II’s 25 year reign over England, shortly before the revolution, tensions slowly began to grow being that he did not have a legitimate issue to become heir to the throne. That implied that the crown would pass to his Catholic brother James which in turn incited the fear of a return to Catholicism.

King James II brought many tensions between the people of England because of the political changes that he made while he reigned as king. Coming into power as a Catholic already brought many concerns to the people because they feared popery and Catholic tyranny. Despite his promises not to allow Catholic influence during his reign he brought in changes. First, King James II allowed Catholics to hold place as officers in the armed forces in November of 1685. Next, the king suspended the Test Acts and therefore allowed him to appoint Catholics as members of his council. In April of 1687, King James passed the Declaration of Indulgence Act which removed all laws against the rights of the Catholics. All of these acts led people to begin to oppose the reign of King James II. Many people rebelled such as seven leading bishops who refused the king’s orders to read his second Declaration of Indulgence. These bishops were arrested their rebellion. All of this led to discontent in the Country and some of those with influence began to search for a new leader in fear of a Catholic monarchy.

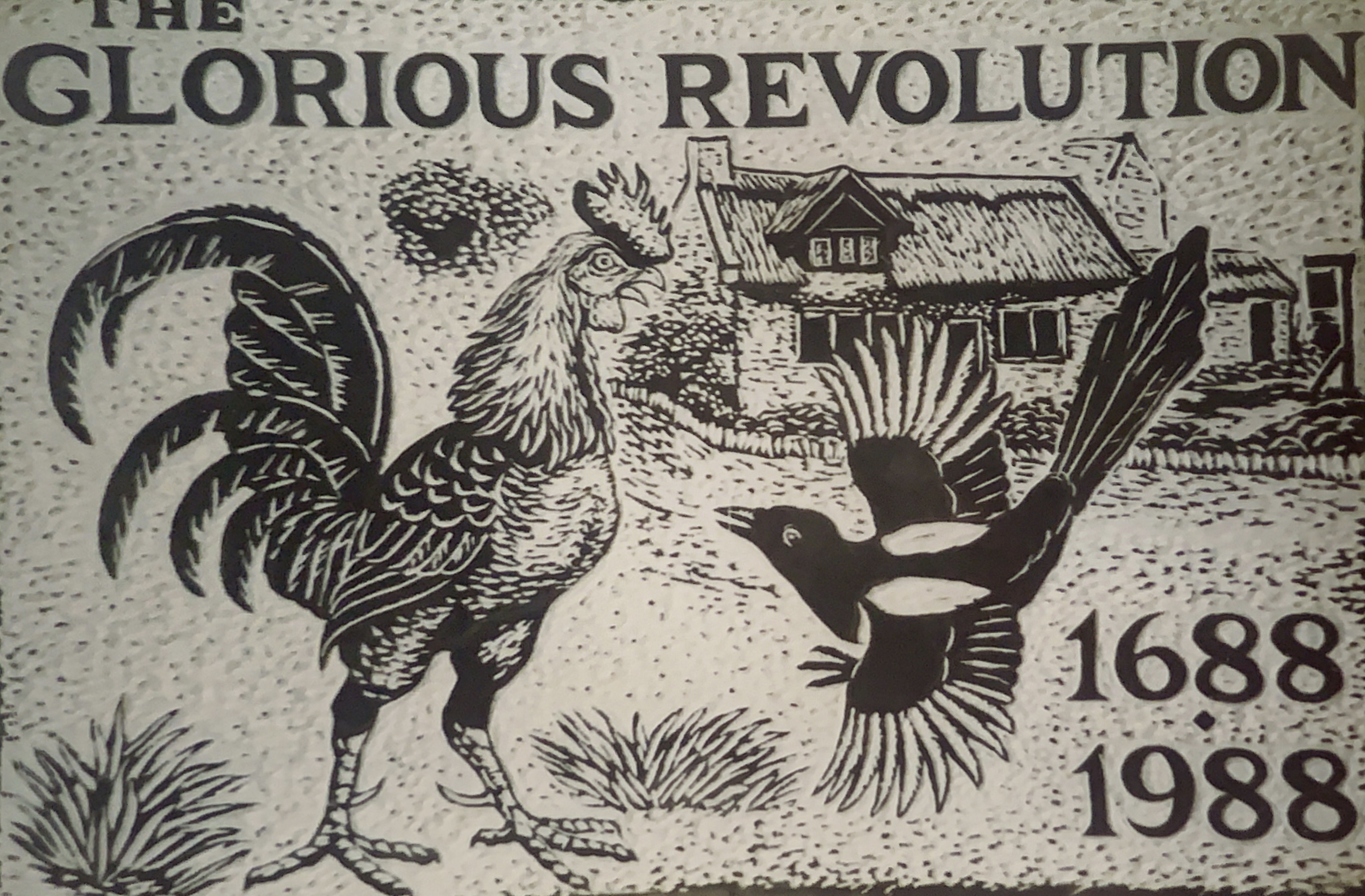

In order to do this, they had to devise a plan. Three of those conspirators, local nobles William Cavendish, 4th Earl of Devonshire, John Darcy, fourth son of the Earl of Holderness, and the Earl of Danby. to meet ostensibly as hunting party, and was planned for Whittington Moor, but when the weather turned stormy, the three men sought refuge at the inn, then an isolated hostelry known as the Cock and Pynot (‘pynot’ being a local term for a magpie). The three men discussed a plan march south against James. They resolved to conspire with other like minded people of influence to write a letter to Prince William.

The signatories were:

- Henry Sydney (who wrote the letter)

- Edward Russell

- Charles Talbot, 12th Earl of Shrewsbury

- William Cavendish, 4th Earl of Devonshire

- Thomas Osborne, 1st Earl of Danby

- Richard Lumley, 2nd Viscount Lumley

- Henry Compton, Bishop of London

The letter, written in code, recorded their plans and invited William to sail to England and take the crown.

History records that James fled at Prince William’s approach, and the so-called Glorious Revolution was a bloodless change of monarch. The Earl of Devonshire was rewarded for his role in the revolution with a dukedom, becoming the 1st Duke of Devonshire.

William made it impossible for any Catholics to vote or hold a seat in the parliament, and made the law, which is still in order today, that the monarch could not be a Catholic or marry someone who was a Catholic. William signed the proposed Bill of Rights that guaranteed certain rights to the citizens of the nation, and he began the change in the English parliamentary to a more democratic one. William’s overthrow of King James and signing of the Bill of Rights made James’ rule the last time that the monarch of England held absolute power. England now had a Protestant monarchy and a system that recognised the importance of Parliament in governing.

One hundred years later, in 1788, a group of dignitaries met at the alehouse to mark the centenary of the Glorious Revolution. The gathering was led by the local vicar, Samuel Pegge, and included the Duke of Devonshire, a direct descendant of the 4th Earl.

The Duke and Duchess led a procession, along with the Mayor of Chesterfield, from Revolution House to a civic reception in Chesterfield. It must have quite a sight, with marching bands and throngs of people stretching the entire three-mile course of the processional route.

Two years later the alehouse was converted into a private dwelling. A new pub was erected directly behind it and named the Cock and Magpie.

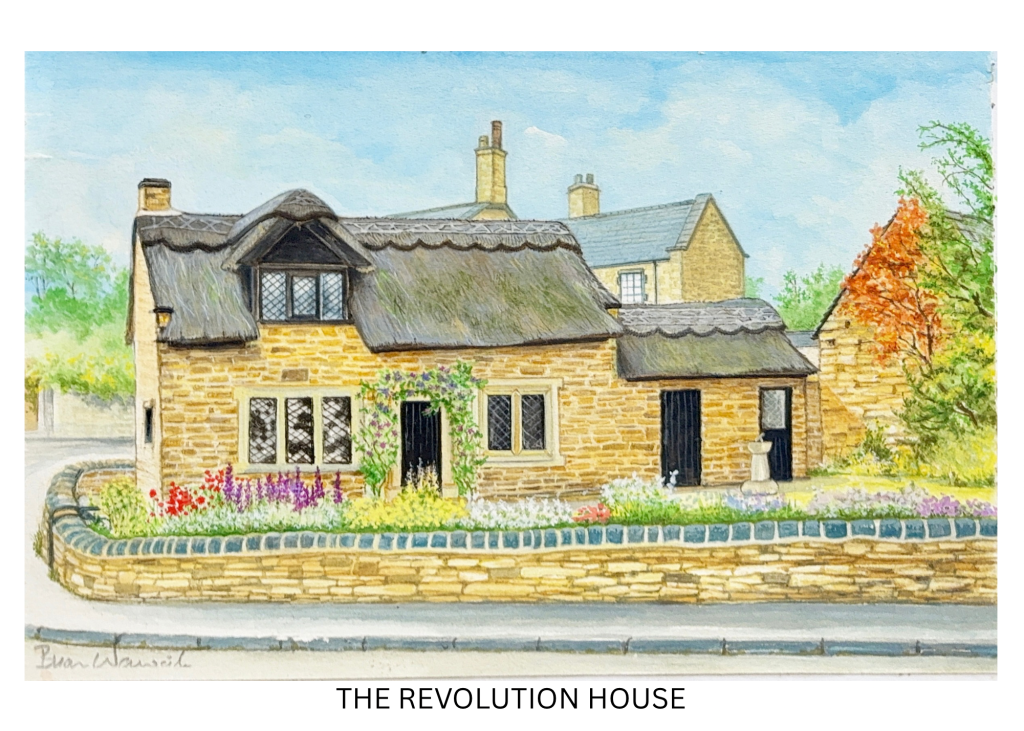

Over the following centuries, the former inn was greatly reduced in size, so that the building we see today is only a fraction of the original Revolution House. There is a parlour on the ground floor, furnished with 17th-century furniture, and an exhibition on the top floor with local history, the story of the building itself, and the tale of the Glorious Revolution.

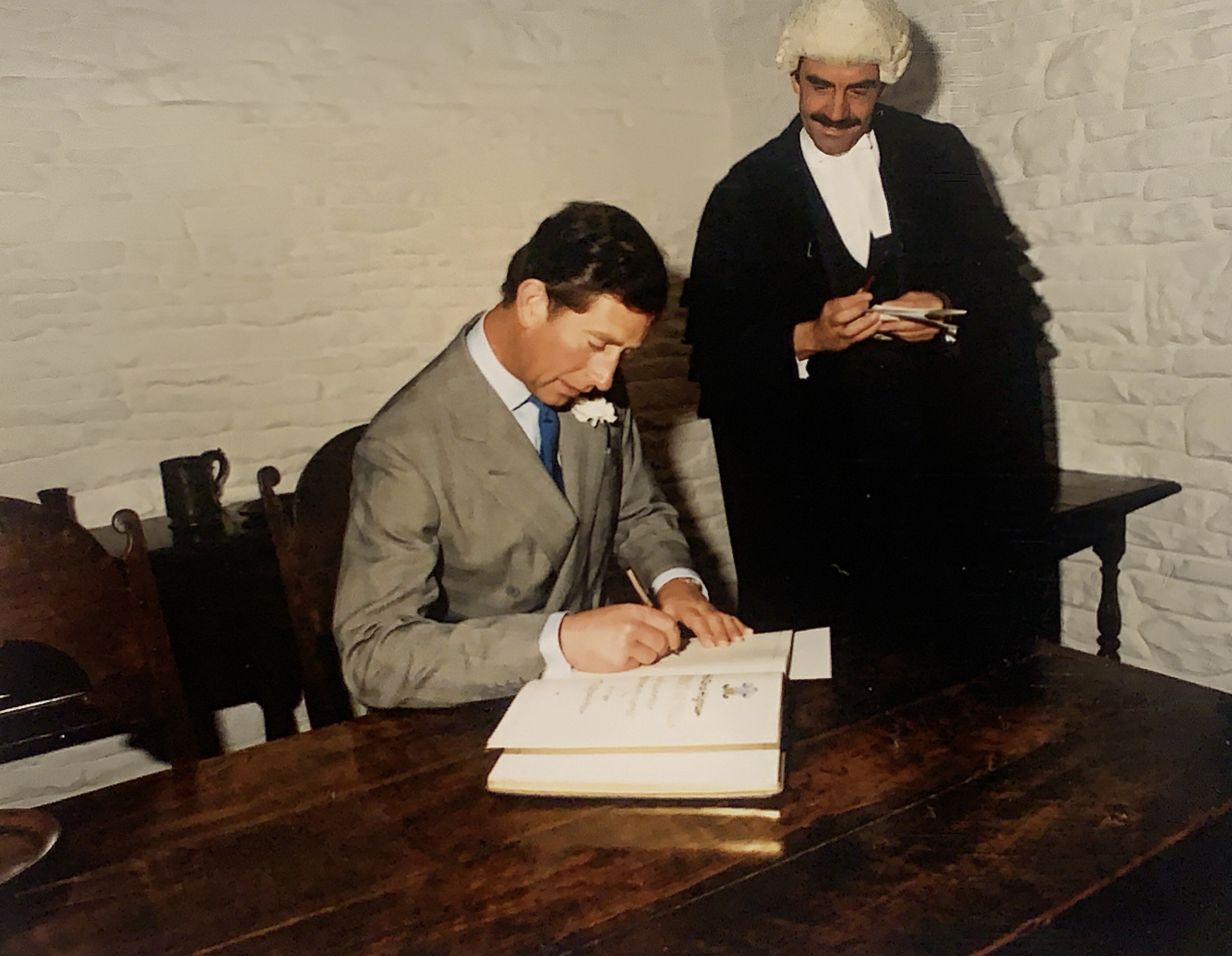

In 1988 a tercentenary celebration was held, with Charles, Prince of Wales in attendance. A limited edition of 300 commemorative plates were made for the occasion, and these have now become prized by collectors.

Some backgound